© WienTourismus/Rainer Fehringer

“We should really go below the surface”

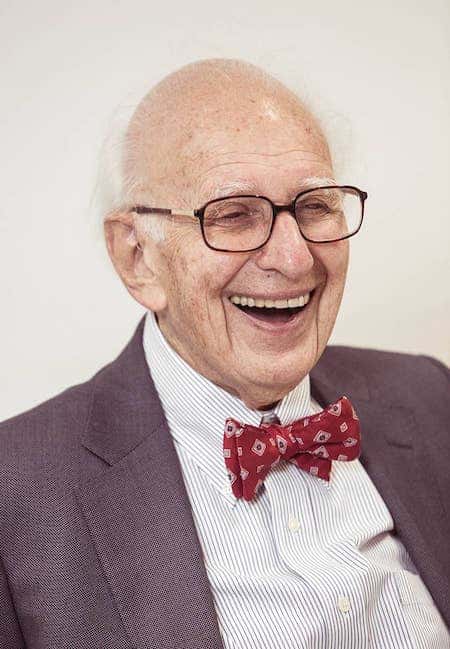

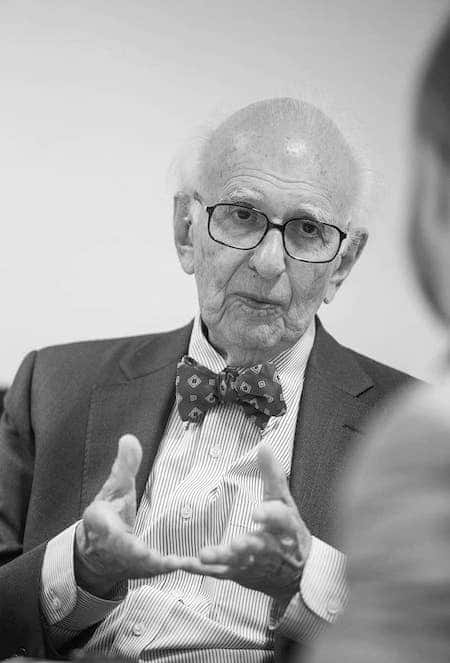

Nobel Prize winner Eric Kandel talks about Viennese Modernism, his preoccupation with the magic of this era and the bite of contemporary werewolves.

Celebrated like a rock star in scientific circles, Eric Kandel is one of the most important brain researchers of the twentieth century. In 2000 he was awarded the Nobel Prize for Medicine for his pioneering work on how memories are stored in the brain. Even at a ripe old age Eric Kandel, who was born in Vienna in 1929, is still an avid researcher and maintains a strong interest in art. The years of Viennese Modernism continue to have a strong hold over him: because it was then that modern research took its first steps into unlocking the secrets of the mind and artists also played a hand in exploring the fundamental principles of thought. In 2012 he published a book entitled The Age of Insight which was devoted to “The Quest to Understand the Unconscious in Art, Mind, and Brain, from Vienna 1900 to the Present”(subtitle).

Mr. Kandel, when was the last time you fell in love with a painting?

Oh my god, I fall in love with paintings all the time. My wife and I have a wonderful collection, we buy art all the time. We picked up a gorgeous Nolde just a few weeks ago.

On a neurological level now, is it actually possible to fall in love with a painting like the 14-year-old Ronald Lauder did with Klimt’s picture of Adele Bloch-Bauer?

Of course it is. You can fall in love with a book, or with wine. You can fall in love with many things. It is not necessarily erotic as it would be between human beings. You get nothing back. But there’s a pleasurable aspect of really liking something.

You also collect Viennese Modernist art …

Yes! I have a very nice Klimt drawing, a Schiele study. And I have several Kokoschkas, including one that was in the Klimt/Schiele/Kokoschka and the Women exhibition at the Belvedere.

What was special about that time?

The Ringstrasse was being built. Vienna was moving and becoming one the most beautiful cities in Europe. Franz Joseph had passed a decree in 1867 declaring that all religions were equal. So the people could travel around the empire. A great many young, ambitious and gifted Jews came to Vienna. And they supported Klimt, Kokoschka and Schiele in a very important way, by having their children and their wives painted by them.

The artists played their part in the discovery of the unconscious, you say. What was their contribution?

They all attempted to portray the unconscious – Kokoschka and Schiele in particular. “I discovered the unconscious independently of Freud,” Kokoschka said. There’s no doubt that he was strongly influenced by Freud.

A light goes off for Kandel: now we have mentioned the name of the man that influenced him, too. The artists put desires, sexuality and emotion on canvas, which Freud had identified as the subconscious drivers behind human behavior. Freud wanted to find out more about the brain. And because he lacked the necessary technical means, he started out by designing a theory of the mind. Kandel continued his work many years later and deciphered the fundamental biological processes in the brain. Freud gave him the impetus for his research.

In 2000 the Nobel Prize for Physiology or Medicine was awarded jointly to KANDEL alongside AVRID CARLSSON of Sweden and PAUL GREENGARD of the USA for their discoveries concerning signal transduction in the nervous system.

© Anders Wiklund/TT NewsAgency/picturedesk.com

When did you first start to deal with Freud?

While I was at college I got to know Anna Kris, the daughter of Ernst Kris1 gearbeitet habe.

What was it about Freud’s work that fascinated you?

Well, the whole idea of an unconscious mental life, the interpretation of dreams. The psychopathology of everyday life. Every slip you make has significance.

- 1Ernst Kris (1900-1957) was an Austrian-born US art historian and psychoanalyst. In 1924 he met Sigmund Freud. In 1938 he emigrated to London and later to the USA. Kris made a major contribution to the psychoanalytic interpretation of artworks.

- 2Sigmund Freud’s practice was located at Berggasse 19 until he emigrated in 1938. It has housed the Sigmund Freud Museum since 1971.

Would you have become a celebrated researcher without him?

Probably not. He influenced every single aspect of my life. My interest as a researcher in finding out more about learning and memory came from psychoanalysis. People always ask me whether psychiatry was useful to me, since I never practiced it. But it influences my everyday thinking.

Why were Freud and Vienna such a good fit?

Although the medical university did not treat him particularly well, he always felt that he received a very good education there. And he liked Berggasse2. He felt very comfortable there. He had a large circle of friends, many of whom were analysts.

Could he have worked in any other city?

No. He did not want to leave, even when Hitler arrived. He wanted to stay, until it was clear that his life was in danger. Because he loved Vienna.

Kandel and Vienna – a special relationship. He grew up at Severingasse 8 close to Berggasse and the Josephinum, which is synonymous with Vienna’s medical achieve-ments. The Belvedere with Schiele’s and Klimt’s pictures was not far away. With the National Socialists in power, Kandel fled to the USA with his family in 1939 at the age of ten. For the rest of his life he would take a critical view of Austria’s suppressed reappraisal of its past. He described becoming an honorary citizen of Vienna in 2009 as ‘bittersweet’.

Kafka described the Viennese Modernism era as a nervous age. What was the psyche of the city like in 1900?

I was not there, so I couldn’t say. But there was a lot of anxiety. Emperor Franz Joseph was on the way down and I think people felt that. Franz Joseph’s relationship with the Kaiser was very much balanced in Germany’s favor. And the idea of going to war frightened many people. And there was actually no need to go to war. Franz Joseph made a serious mistake in doing so. It destroyed Austria, beyond the end of the Second World War.

The Habsburg monarchy was a large empire, but Vienna was a relatively small city. Would you agree that its size made it the perfect incubator for a fruitful relationship between science and art?

Yes. Because people could meet there. Researchers working at the university would go to the coffeehouses and carry on their conversations there. In Vienna there was easy movement from an academic to a social context.

So it is no coincidence that the magic of this era – as you put it – played out in Vienna?

No, the city was the right setting for it.

And everyone is talking about the famous names. Klimt, Schiele, Schnitzler …

… and Otto Wagner.

But you are one of only a handful of people who talk about Carl von Rokitansky, the great nineteenth century pathologist who had access to every dead body in the city.

Yes, fantastic. He is still not appreciated fully. The Josephinum put on an exhibition that took my thinking as its point of departure.

ERIC KANDEL at an interview at the Institute of Molecular Biotechnology in Vienna.

© WienTourismus/Rainer Fehringer

Rokitansky was so influential because he was the first to take a systematic look beneath the skin, taking medicine away from philosophy and towards a fact-based modern discipline.

Not just that. He was a good spokesman for science and highly progressive: an outstanding person and a great leader of the Vienna Medical School.

Do you think modernism could have happened without him?

I think it’s hard to say that any person is responsible for that period. You know, if it wasn’t for him we would never have had a Zuckerkandl salon, where countless artists heard about the latest scientific discoveries. I think we have to put him in that mix. Let’s put it like this, he was very important.

Praising Rokitansky – something Kandel likes to do. In his book The Age of Insight, he highlights the former's influence on the genesis of modern medicine. Born in Bohemia, Rokitansky was liberal, tolerant and cosmopolitan – and strongly oriented to fundamental scientific principles. He was an advocate of interdisciplinary collaboration, and never lost sight of patient needs. Kandel would also like to be remembered as a builder of bridges: between the disciplines that focus on the brain and the mind.

Where does the artists’ fascination for scientific insights stem from? Were they more open on an elementary level or was it just in their instincts to be where change was happening?

I think the latter. Artists had expressed an interest in science long before that.

You once said that Oskar Kokoschka burst onto the Viennese art scene like a werewolf at a ladies’ circle. Are werewolves like that still around today?

Yes, there are some great people out there. Lucian Freud, for example. Jeff Koons, who is a good friend of mine, is a very unusual artist with enormous talent.

Could art play a similar role today?

I’m sure it could. Although art is not as unified any more. But I can give you an example: I have just written a book on abstract expressionism. The New York art scene was like this between 1940 and 1960.

What is left of Viennese Modernism? What is its most important message?

That we should really go below the surface and study things deeply. Which is what they did. The message to society is that it is important for people to learn what science is about.

How much do we know about the human brain?

I would say that we have deciphered around ten percent of it.

Will we manage to fully understand it one day?

Why not?